Working Papers

Employment Denial as Repression: Evidence from Argentina's Film Industry

[Working paper]

Though dictators have a spectrum of repressive tools available to them, we know less about the logic and effects of nonviolent repression. I focus on one such tactic, employment repression, or government efforts to block potential critics from working. I argue that employment repression minimizes the influence of prominent critics, making them less threatening to the regime even if they should dissent. To support this theory, I match data on film productions with lists of artists barred from working under Argentina's military dictatorship (1976-1983). Results show that the regime targeted more prominent artists, and that employment repression restricted victims' public profiles and isolated them from their networks. Evidence from theater suggests that this did not stop public dissent, but it did limit victims' reach. These findings expand our understanding of the repertoire of repression, and particularly the logic of nonviolent methods in suppressing dissent.

Though dictators have a spectrum of repressive tools available to them, we know less about the logic and effects of nonviolent repression. I focus on one such tactic, employment repression, or government efforts to block potential critics from working. I argue that employment repression minimizes the influence of prominent critics, making them less threatening to the regime even if they should dissent. To support this theory, I match data on film productions with lists of artists barred from working under Argentina's military dictatorship (1976-1983). Results show that the regime targeted more prominent artists, and that employment repression restricted victims' public profiles and isolated them from their networks. Evidence from theater suggests that this did not stop public dissent, but it did limit victims' reach. These findings expand our understanding of the repertoire of repression, and particularly the logic of nonviolent methods in suppressing dissent.

Criminal Fragmentation in Mexico (R&R at Political Science Research & Methods)

Mexico’s "war on drugs" is increasingly characterized by small, local groups rather than large cartels. However, understanding such fragmentation is challenging precisely be- cause of the number of actors involved. This research note introduces data on more than 450 criminal groups operating in Mexico between 2009 and 2020. I use the dataset to test prominent theories about when criminal landscapes become more fragmented: following the removal of kingpins, and in response to profit opportunities (here, fuel theft). Both are associated with more groups operating in affected regions, with king- pin removals correlating with the emergence of new groups and profit opportunities attracting existing organizations. This research contributes to our understanding of criminal control and informs debates over policies aimed at reducing violence.

Agents of Judicial Repression (w/ Fiona Shen Bayh)

[Paper available on request]

What causes fragmentation in criminal conflicts? Mexico's "drug war" has become increasingly characterized by small, local groups rather than large, organized cartels. However, this has made it difficult to quantitatively document when and why fragmentation occurs. This article uses novel, municipal-level data on more than 500 criminal groups operating in Mexico between 2009 and 2020 to explore when groups emerge or expand their territory. Developed from narcoblogs, anonymous citizen journalism websites, I use this dataset to test two prominent theories about when criminal landscapes become more fragmented. First, I show that negative shocks -- the capture of kingpins -- are correlated with more groups, both large and small, operating in the affected organization's territories. However, these effects persist only for smaller outfits, in part because major cartels become increasingly decentralized. Second, I show that positive shocks -- here energy sector liberalization, which increased the profitability of fuel theft -- attracted both large and small groups to affected municipalities, and did not lead to decentralization. These findings point to the benefits of disaggregating types of criminal actors, advancing our understanding of conflict and fragmentation.

What causes fragmentation in criminal conflicts? Mexico's "drug war" has become increasingly characterized by small, local groups rather than large, organized cartels. However, this has made it difficult to quantitatively document when and why fragmentation occurs. This article uses novel, municipal-level data on more than 500 criminal groups operating in Mexico between 2009 and 2020 to explore when groups emerge or expand their territory. Developed from narcoblogs, anonymous citizen journalism websites, I use this dataset to test two prominent theories about when criminal landscapes become more fragmented. First, I show that negative shocks -- the capture of kingpins -- are correlated with more groups, both large and small, operating in the affected organization's territories. However, these effects persist only for smaller outfits, in part because major cartels become increasingly decentralized. Second, I show that positive shocks -- here energy sector liberalization, which increased the profitability of fuel theft -- attracted both large and small groups to affected municipalities, and did not lead to decentralization. These findings point to the benefits of disaggregating types of criminal actors, advancing our understanding of conflict and fragmentation.

Reel Politik: The Hollywood Blacklist and Democratic Repression

[Paper available upon request]

Can politicians in democracies punish citizens for political beliefs, despite civil liberties protections? If so, how? I argue that politicians partner with radical non-governmental groups for the purpose of political suppression. I test this theory with evidence from the ``Hollywood Blacklist" of the 1950s, which developed from the work of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Pairing archival records with an online movie database, I first establish that being named during committee proceedings had significant negative impacts on victims. The committee also had a broader chilling effect on political themes in film. Qualitative and quantitative evidence shows how Congress partnered with radical anti-communist groups to enforce and grow the lists, through pressure campaigns that threatened boycotts and picketing. As a result, the lists primarily impacted visible onscreen talent. That these efforts were significantly more effective than past attempts by non-governmental groups highlights the role of politicians in empowering civil society. My results have implications for how even strong democratic institutions can be misused.

Can politicians in democracies punish citizens for political beliefs, despite civil liberties protections? If so, how? I argue that politicians partner with radical non-governmental groups for the purpose of political suppression. I test this theory with evidence from the ``Hollywood Blacklist" of the 1950s, which developed from the work of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Pairing archival records with an online movie database, I first establish that being named during committee proceedings had significant negative impacts on victims. The committee also had a broader chilling effect on political themes in film. Qualitative and quantitative evidence shows how Congress partnered with radical anti-communist groups to enforce and grow the lists, through pressure campaigns that threatened boycotts and picketing. As a result, the lists primarily impacted visible onscreen talent. That these efforts were significantly more effective than past attempts by non-governmental groups highlights the role of politicians in empowering civil society. My results have implications for how even strong democratic institutions can be misused.

Repression and Cultural Memory: Individual-Level Evidence from Argentina

[Working paper available on request]

Recent literature establishes that authoritarian repression has long-term political effects at both the individual and community level. I extend this research by documenting how repression influences the politics of memory. I argue that individuals targeted by the dictatorship should engage more in activities aimed at addressing the authoritarian past, due to both individual motivation and structural factors. I test this theory in the case of Argentina, by matching archival data on repression with IMDb information on careers. I provide evidence that artists targeted by the government were more likely to produce movies and television that addressed the authoritarian past post-democratization. These results are not only due to ideology: results persist even when considering only artists deemed by the secret police to have similar ideological backgrounds. My findings demonstrate how repression shapes the production of national memory at the individual-level.

Recent literature establishes that authoritarian repression has long-term political effects at both the individual and community level. I extend this research by documenting how repression influences the politics of memory. I argue that individuals targeted by the dictatorship should engage more in activities aimed at addressing the authoritarian past, due to both individual motivation and structural factors. I test this theory in the case of Argentina, by matching archival data on repression with IMDb information on careers. I provide evidence that artists targeted by the government were more likely to produce movies and television that addressed the authoritarian past post-democratization. These results are not only due to ideology: results persist even when considering only artists deemed by the secret police to have similar ideological backgrounds. My findings demonstrate how repression shapes the production of national memory at the individual-level.

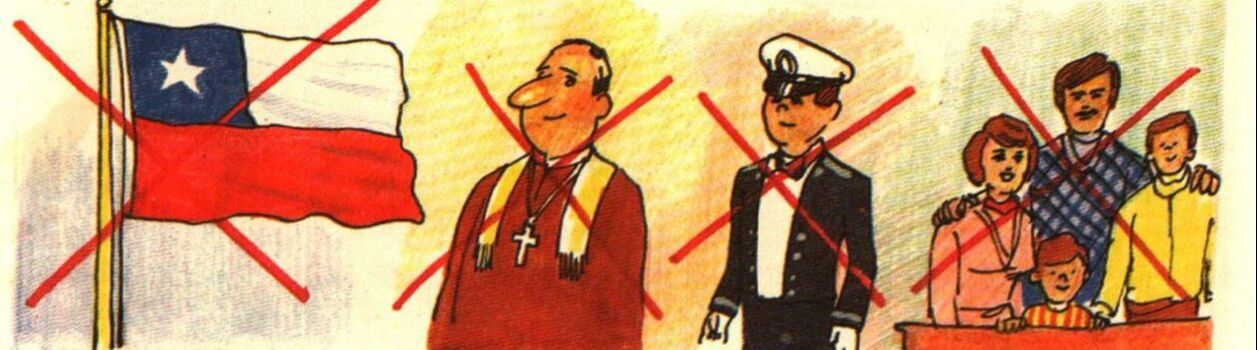

The Audience of Repression: Killings and Disappearances in Pinochet's Chile

[Working paper]

Authoritarianism literature emphasizes that repression suppresses dissent, while co- optation builds support. This paper theorizes that repression can serve not just to eliminate opposition, but to appeal to supporters. I argue that regimes can use political killings to justify rule, by demonstrating a danger to the state that requires authoritarian controls to manage. I test this with evidence from Chile, where the military government enjoyed support on the basis of fighting an exaggerated communist threat. Original data on the regime’s 3,000 victims shows that killings were more likely in high-support areas – wealthy, conservative districts – but targeted suspicious individuals, signaling a direct threat to supporters. Evidence additionally shows that repression increased in high-support areas following a negative shock to support; public arrests were more likely in high-support districts; and the regime fabricated subversive activities to inflate threat. By incorporating authoritarian supporters, this research improves our understanding of subnational patterns of violence.

Authoritarianism literature emphasizes that repression suppresses dissent, while co- optation builds support. This paper theorizes that repression can serve not just to eliminate opposition, but to appeal to supporters. I argue that regimes can use political killings to justify rule, by demonstrating a danger to the state that requires authoritarian controls to manage. I test this with evidence from Chile, where the military government enjoyed support on the basis of fighting an exaggerated communist threat. Original data on the regime’s 3,000 victims shows that killings were more likely in high-support areas – wealthy, conservative districts – but targeted suspicious individuals, signaling a direct threat to supporters. Evidence additionally shows that repression increased in high-support areas following a negative shock to support; public arrests were more likely in high-support districts; and the regime fabricated subversive activities to inflate threat. By incorporating authoritarian supporters, this research improves our understanding of subnational patterns of violence.